Throughout human history, some art has been a profound source of awe and wonder. From the cave paintings of Lascaux to the Sistine Chapel ceiling, and from Van Gogh’s swirling night skies to Handel’s Messiah, art transcends language and cultural boundaries to evoke powerful emotional responses. Why does art move us so deeply? The answer lies in the workings of the human brain, the phenomenon of awe, and its evolutionary significance.

The neurology of awe in art

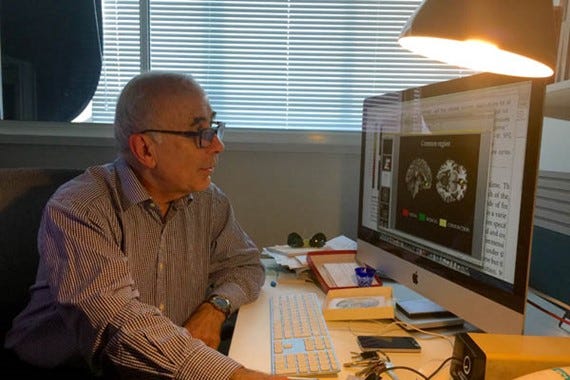

When we encounter art that inspires awe, multiple brain regions activate. The default mode network (DMN), responsible for introspection and self-referential thought, quiets during awe-inspiring experiences. This diminishes the sense of self and expands awareness, explaining why people often describe feeling small yet deeply connected to a larger whole when engaging with monumental art or natural beauty.

David Cycleback: Big Ideas is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Subscribed

Awe engages the prefrontal cortex to process the novel and vast elements of artwork, integrating new information. Simultaneously, the ventral striatum, part of the brain’s reward system, releases dopamine, reinforcing feelings of pleasure and fascination.

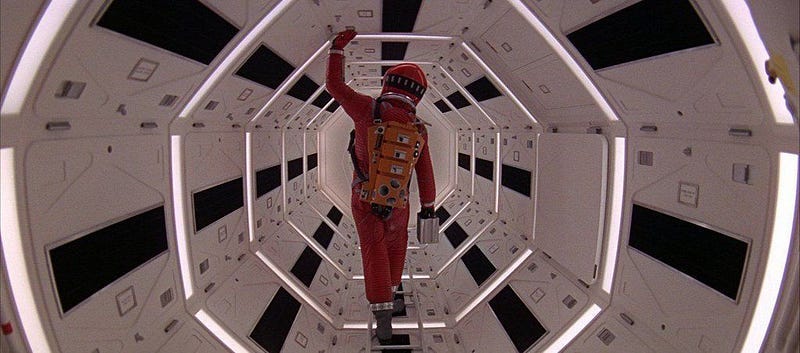

Art often challenges mental frameworks through innovative techniques, surreal compositions, or monumental scale. Hieronymus Bosch’s fantastical worlds and Yayoi Kusama’s infinity rooms, for example, invite viewers to confront the unfamiliar and expand their understanding of reality. Similarly, a colossal statue like Michelangelo’s David or the Sphynx invokes a sense of scale that dwarfs individual concerns.

Art that inspires awe often draws us into shared narratives or universal themes, creating a sense of connection. Neuroscientific studies reveal that the suppression of the DMN during awe-inducing experiences reduces egocentrism and promotes feelings of unity. Mark Rothko’s color field paintings, with their seemingly simple compositions, often evoke profound emotional depths that transcend cultural and individual differences.

The evolutionary role of awe

Awe has played an important role in human evolution. Its development can be linked to several survival and social benefits.

Enhancing social cohesion is one benefit. Awe-inspiring events often bring people together, whether it’s witnessing a natural phenomenon like a solar eclipse or participating in collective rituals like music or dance. Such shared experiences strengthen social bonds, which are crucial for survival in cooperative groups. Moreover, awe reduces self-focus, encouraging people to prioritize the group’s needs over personal desires, fostering cooperation and mutual support.

Awe encourages learning and exploration. It often arises in response to novel and vast stimuli, motivating individuals to explore and learn about their environment. For early humans, understanding natural phenomena and unfamiliar territories increased survival odds. Experiencing awe enhances memory and learning by activating the hippocampus, which helps assimilate new knowledge in the brain.

Strengthening survival strategies is another function of awe. Awe-inducing experiences capture attention and enhance focus. Observing a vast thunderstorm or volcanic eruption heightens awareness of potential dangers and improve preparedness. Awe also shifts perspective from immediate concerns to larger contexts, helping humans plan for the future, such as stockpiling resources or building protective shelters.

Awe has long been associated with spiritual and religious experiences. For early humans, interpreting awe as a connection to higher powers unified social groups.

The benefits of awe and art

In the modern world, awe serves as an antidote to stress and disconnection. Research shows that experiencing awe can lower cortisol levels, reduce inflammation, and improve overall well-being. Art galleries, public sculptures, and digital art platforms provide accessible avenues for encountering awe in daily life. Moreover, creating art can be equally powerful. The process of artistic expression engages similar neural pathways, encouraging mindfulness and a sense of flow.

References

“Neuroaesthetics: A Methods Based Introduction” (Springer)

“The Science of Awe” (Greater Good Science Center, UC Berkeley)

“Dynamics of brain networks in the aesthetic appreciation” (National Academy of Sciences)

“Awe as a Pathway to Mental and Physical Health” (National Library of Science)