Abstract art focuses on fundamental visual elements such as color, shape, and form, moving away from literal representation to evoke emotions, ideas, and aesthetic experiences. By removing recognizable imagery, it invites personal interpretation and engages the brain differently from purely representational art.

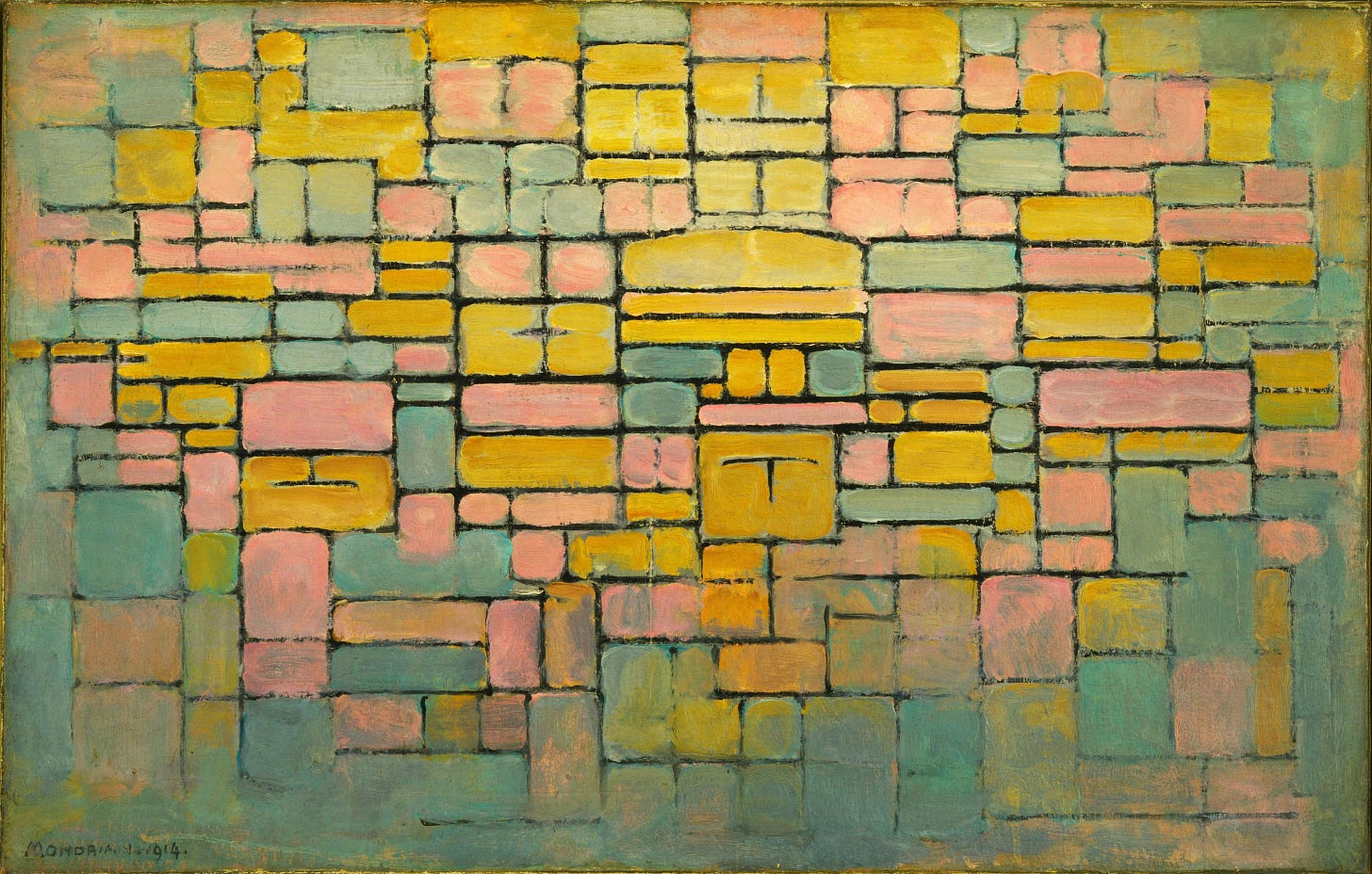

Some pieces are entirely non-representational, while others simplify or distort real-world elements to capture their essence. It ranges from partially abstract depictions, such as Paul Cézanne’s landscapes, to the fully non-representational works of Piet Mondrian.

Historically, Western art was dominated by realistic representation. Technical skill was measured by the ability to create lifelike depictions of landscapes or still lives, and the viewer easily identified an artwork’s subject and objects.

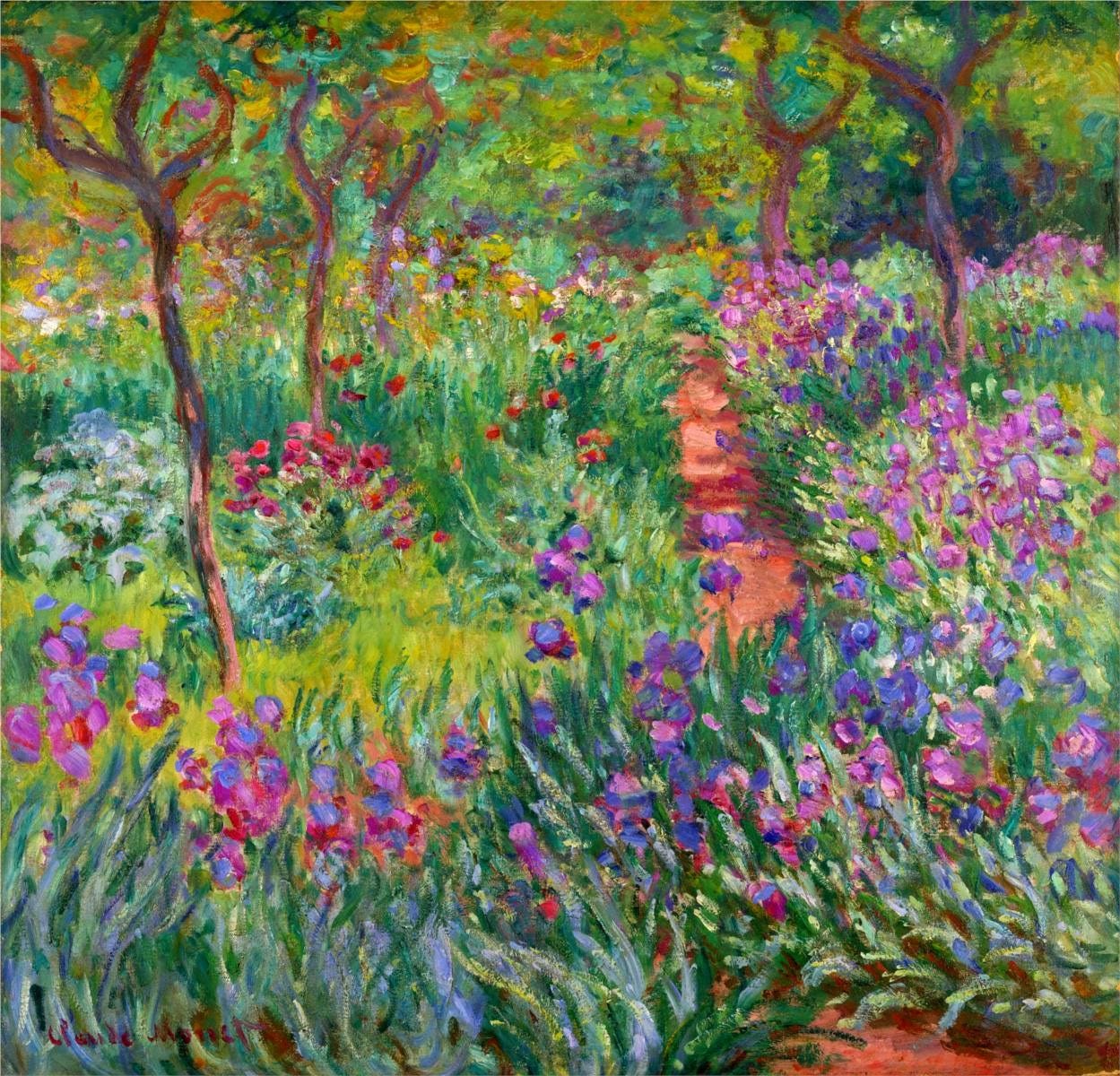

The rise of impressionism in the 1870s marked a turning point. Led by artists such as Monet and Renoir, this movement emphasized light, atmosphere, and expressive brushwork over precise detail. Impressionism broke away from realism by capturing fleeting moments and subjective impressions and paved the way for modern abstraction.

The Russian Wassily Kandinsky was long regarded as the first truly abstract painter until Hilma af Klint’s works were rediscovered in the 1980s. The Swedish Klint began creating abstract art in 1906. Both deeply religious, Hilma and Kandinsky used their paintings to try to express spiritual ideas.

An academic, Kandinsky scientifically studied how qualities such as color, shape, and position affected emotions. University College London neurobiologist Semir Zeki said that, though they may not have realized it, all great artists were neuroscientists. They used angles, symbols, colors, and other qualities to influence the audience’s minds.

The brain’s reaction to abstract art

The human brain instinctively seeks recognizable patterns and meaning. Abstract art challenges this tendency, requiring viewers to find meaning in ambiguity. While some find this process stimulating, others struggle with it. Though artists, such as Rothko and Kandinsky, tried to express particular feelings or abstract ideas to the viewer, abstract art is up to personal interpretation. This is true with all art, but especially with abstract art.

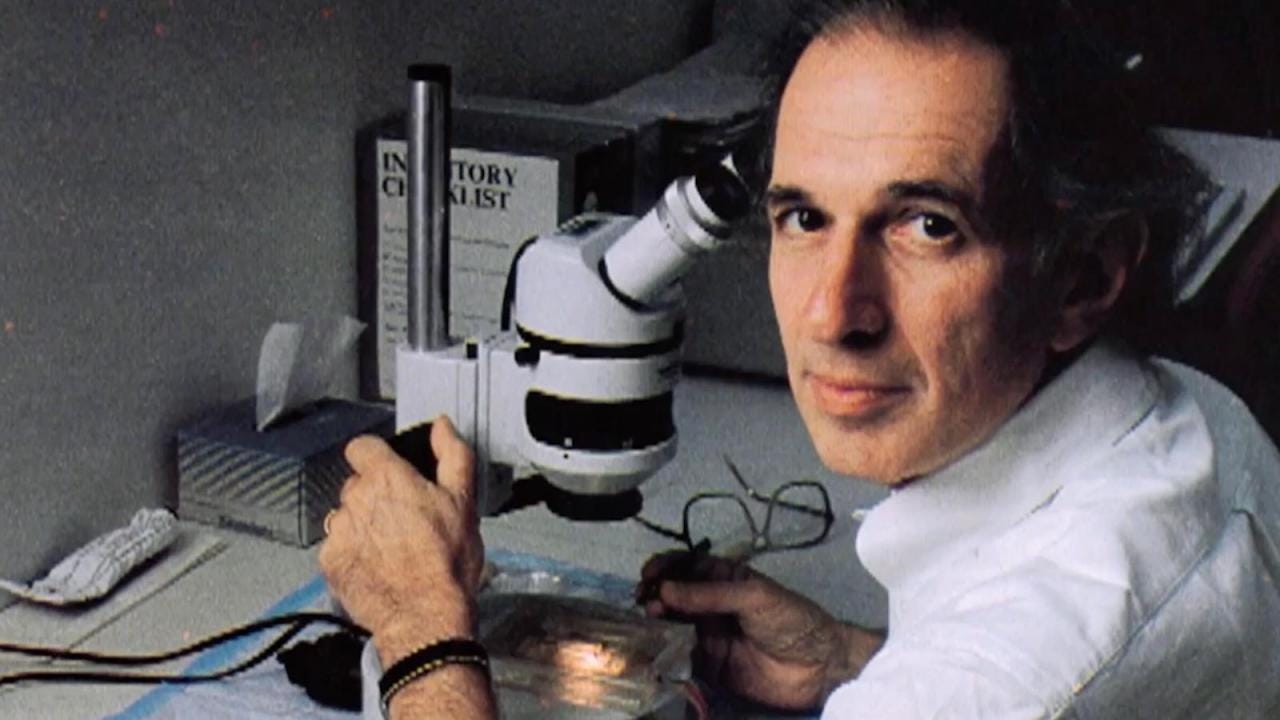

Nobel Prize winner Eric Kandel, a Columbia University professor of neuroscience and psychiatry, identified two cognitive processes involved in art perception: bottom-up and top-down processing. Bottom-up processing focuses on basic visual elements like color and spatial relationships, making it central to abstract art. In contrast, top-down processing, which draws on personal experience and knowledge, plays a larger role in representational art. Abstract art minimizes or even removes top-down processing by removing realistic images.

Neuroscience studies show that abstract art activates multiple brain regions, and the viewer’s brain processes abstract art differently than it does realistic art. The occipital lobe processes basic visual details like color and shape, while areas like the fusiform face area (FFA) and parahippocampal place area (PPA) identify patterns—even in the absence of clear forms. The prefrontal cortex manages the cognitive effort needed to interpret abstract visuals, while the cingulate cortex resolves ambiguity. The limbic system contributes to emotional responses.

Viewing abstract art is good for you

Interacting with abstract art provides cognitive and emotional benefits. Its open-ended nature stimulates creativity, problem-solving, and mental flexibility, while its ambiguity encourages mindfulness and stress reduction. As with other activities, such as meditation, or learning a new skill or language, practicing viewing art is good for you.

References

“What does the brain tell us about abstract art?” (National Library of Medicine)

“Beauty and the Brain: The Emerging Field of Neuroaesthetics” (Harvard University)

“This is your brain on art” (Salon)

“Researchers find abstract art evokes a more abstract mindset than representational art” (Medical Xpress)

“Bridging Neuroscience and Abstract Art: Eric Kandel” (Vienna Contemporary Magazine)